Introducción

Las tasas de infección del sitio quirúrgico (ISQ) después de una mastectomía son más altas de lo esperado para procedimientos limpios, con reportes de hasta el 26% [1-6]. Además de los factores de riesgo de infección propios del paciente, tales como obesidad y tabaquismo [7,8], la presencia de un drenaje quirúrgico y su uso prolongado, se asocia también con un riesgo aumentado de infección [5,9,10].

Algunos cirujanos han recomendado profilaxis antibiótica postoperatoria hasta que los drenajes son removidos, pero esa práctica puede seleccionar organismos resistentes, sin impactar sobre la tasa de infección [11-13]. Además, el uso prolongado de antibióticos conlleva otras consecuencias, incluyendo reacciones alérgicas, intolerancia gastrointestinal, infección por hongos e infección por Clostridium difficile [14]. Los autores de este trabajo presumieron que la colonización bacteriana de los drenajes quirúrgicos, contribuye a la ISQ después de la cirugía mamaria y que las medidas locales de antisepsia, eran probablemente bien toleradas y efectivas para reducir la colonización del drenaje y las tasas de ISQ. En consecuencia, llevaron a cabo un ensayo prospectivo, randomizado, controlado, ciego para el cirujano, para determinar si las simples medidas de antisepsia local, podían reducir efectivamente la colonización bacteriana de los drenajes después de la cirugía mamaria.

Métodos

Población en estudio

Después de la aprobación del Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, se reclutaron prospectivamente a los sujetos elegibles, de la práctica quirúrgica mamaria en la Clínica Mayo de Rochester, MN, entre enero de 2009 y mayo de 2011. Los individuos fueron incluidos si eran sometidos a una mastectomía total y/o disección de los ganglios linfáticos axilares, por enfermedad benigna o maligna, en los que fueron colocados drenajes. Los sujetos eran no elegibles si estaban embarazadas, habían recibido antibióticos dentro de los 14 días previos a la cirugía, tenían alergia conocida a la clorhexidina o eran sometidas a reconstrucción inmediata (debido al uso común de antibióticos postoperatorios en ese subgrupo).

Randomización

Después del consentimiento informado, los sujetos fueron randomizados, tanto para el régimen estándar de cuidado del drenaje, como para el régimen de antisepsia del drenaje, por medio de un programa computarizado de randomización, usando asignación dinámica y estratificación por procedimiento quirúrgico (mastectomía o lumpectomía con disección axilar), cirujano e índice de masa corporal (IMC <30 o ≥30). En el caso de procedimientos bilaterales, las pacientes con cáncer unilateral tuvieron recolección de muestra y análisis del lado afectado con cáncer. Los sujetos con cáncer bilateral o mastectomía profiláctica bilateral fueron sometidos a randomización computarizada para seleccionar el lado a ser evaluado en el estudio. El cirujano que operaba permaneció ciego en relación con la rama de tratamiento asignada.

Estandarización perioperatoria

Todos los sujetos recibieron una dosis preoperatoria de cefazolina endovenosa (dosificada por peso) dentro de los 30 minutos antes de la incisión de piel. En caso de alergia a la cefazolina, se alternó con vancomicina o levofloxacina y los antibióticos fueron repetidos intraoperatoriamente, cuando se consideró apropiado. La piel se preparó con clorhexidina/alcohol (ChloraPrep, CareFusion Corporation, San Diego, CA) o con iodo/alcohol (DuraPrep, 3M, St Paul, MN), de acuerdo con la preferencia del cirujano. El drenaje utilizado fue un tubo redondo sin canal central de 15F, asegurado con sutura monofilamento no reabsorbible. No se permitieron los antibióticos más allá de las 24 horas después de la cirugía. Las pacientes pudieron ducharse 48 horas después de la operación pero no se permitió el baño de inmersión.

Regímenes de cuidado del drenaje

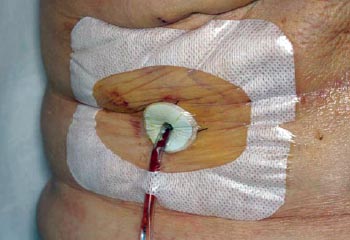

Los sujetos del estudio y miembros de la familia recibieron instrucciones personales sobre el cuidado del drenaje, en el primer día postoperatorio (DPO), por parte de la enfermera coordinadora y se les advirtió de no divulgar el régimen de cuidado del drenaje a su cirujano. Todos los sujetos en ambas ramas de tratamiento fueron instruidos para estirar el tubo de drenaje, vaciar el bulbo y registrar el volumen de líquido, al menos dos veces al día. Los individuos asignados para el cuidado estándar del drenaje, también fueron advertidos para limpiar el sitio de salida del mismo con hisopos preparados con alcohol isopropílico 70%, 2 veces al día y no cubrirlo con gasa estéril. A los sujetos asignados para el cuidado antiséptico del drenaje se les mostró como limpiar el sitio de salida del mismo con alcohol y luego aplicar un disco de gluconato de clorhexidina (Biopatch, Johnson & Johnson Medical) en dicho sitio y asegurarlo con un apósito oclusivo adhesivo transparente estéril (Fig. 1). El disco de clorhexidina y el apósito oclusivo fueron cambiados cada 3 días hasta la remoción del drenaje. Además, los sujetos en la rama de antisepsia fueron instruidos para realizar una irrigación antiséptica del bulbo, 2 veces al día, de la siguiente manera: instilación de 10 mL de solución diluida de Dakin (0,0125% de hipoclorito de sodio tamponado) en el bulbo del drenaje, a través de la válvula de salida (preparada con alcohol), sacudir ocasionalmente por más de 10 minutos y luego vaciar el bulbo y retornarlo a la succión. Al momento de la ducha, el disco de clorhexidina/apósito oclusivo fue dejado intacto.

Figura 1: Disco de clorhexidina cubierto con un apósito oclusivo adherente

Manejo de drenajes múltiples

Si se colocó más de un drenaje por sitio quirúrgico (por ej., 2 drenajes en el escenario de una mastectomía radical modificada), ambos drenajes asociados con ese sitio quirúrgico, fueron tratados de acuerdo con la rama asignada. Cada drenaje asociado con el sitio quirúrgico fue evaluado separadamente para el objetivo final de colonización bacteriana.

Visitas de seguimiento y cultivos

Durante 30 días después de la operación, se completó en cada visita de seguimiento un formulario estandarizado de recolección de datos, con detalles incluyendo volumen de drenaje, eritema o cambios en la piel en los sitios de la incisión y del drenaje y evidencia de seroma o infección. Además, el registro médico fue revisado para detectar infecciones tardías. El ocultamiento al cirujano fue mantenido durante las visitas postoperatorias por el coordinador del estudio, removiendo todos los materiales de curación antes de la evaluación del cirujano. Se estableció una visita obligatoria de seguimiento a la semana (en DPO 7 ± 1) para estudio de los cultivos y para evaluación clínica de signos de infección o reacciones adversas al régimen de antisepsia del drenaje. Si los drenajes estaban listos para ser removidos antes de eso, todos los cultivos se obtenían el día del retiro del drenaje. En cada visita se investigó el cumplimiento de las intervenciones antisépticas por parte del coordinador del estudio, quien preguntó a las pacientes si habían tenido alguna dificultad que impidiera completar el régimen prescripto. En las pacientes con evidencia clínica de infección, se realizaron los cultivos diagnósticos y la terapia antibiótica de rutina. Las guías para la remoción del drenaje especificaban un débito de 30 mL o menor en 24 horas por 2 días consecutivos, o el 19º DPO, lo que sucediera primero. Si no se removía el drenaje en la visita postoperatoria de la 1º semana, entonces se obtenía un nuevo cultivo del líquido de drenaje el día del retiro del tubo; por lo tanto, algunos sujetos tuvieron cultivos del líquido de drenaje en 2 momentos diferentes. Los cultivos de los tubos de drenaje y su remoción fueron añadidos al protocolo, después de que el estudio estuviera en marcha y estuvieron disponibles en 76 de 100 pacientes.

Microbiología

En la visita de la 1º semana, se obtuvieron asépticamente 2 mL de muestra del líquido de drenaje del bulbo, para cultivos semicuantitativos aeróbicos y anaeróbicos. El día de retiro del drenaje, se obtuvieron cultivos tanto del líquido en el bulbo como del tubo de drenaje. Los drenajes fueron removidos de manera estéril, después de preparación con clorhexidina y drapeado estéril del sitio del drenaje. Se tomó una porción subcutánea de 5 cm del tubo de drenaje, comenzando aproximadamente a 1-2 cm por dentro del sitio de salida en la piel.

Para el cultivo del líquido de drenaje, se inocularon 1 o 2 gotas en placas de agar con sangre de oveja, eosina-azul de metileno y colistina-ácido nalidíxico, y en placas de agar anaeróbicas con sangre de oveja y 1 mL de líquido de drenaje fue inoculado en caldo de tioglicolato. Las placas de agar aeróbicas fueron incubadas a 35ºC en CO2 al 5-7% por 4 días, o hasta la positivización. La placa de agar anaeróbica fue incubada anaeróbicamente por 7 días o hasta la positivización. El caldo de tioglicolato fue incubado anaeróbicamente por 14 días o hasta la positivización. El crecimiento fue reportado como negativo, crecimiento sólo en el caldo o crecimiento en la placa y fue cuantificado como 1+, 2+, 3+ o 4+, de acuerdo con el protocolo estandarizado de laboratorio. Todos los aislamientos fueron especificados.

Para el cultivo del tubo de drenaje, el tubo fue rodado sobre la superficie de una placa de agar con sangre de oveja, 4 veces, en diferentes direcciones [15] y la placa incubada aeróbicamente a 35ºC en CO2 al 5-7%, por 4 días o hasta la positivización. El crecimiento fue identificado y reportado semicuantitativamente como menos de 10 unidades formado colonias (CFU), 10 a 19 CFU, 20 a 50 CFU, 51 a 100 CFU o más de 100 CFU. El personal de laboratorio desconocía los regímenes de cuidado del drenaje de las pacientes y los resultados de los cultivos no fueron reportados o incluidos en los registros médicos de los participantes.

Objetivos finales y poder estadístico

El objetivo final primario de este estudio fue el crecimiento bacteriano en el líquido del bulbo del drenaje en la visita de seguimiento en la 1º semana. Estimando una tasa de colonización bacteriana del 33% en el líquido de drenaje la 1º semana, se proyectó un tamaño de muestra de 100 pacientes, para brindar un poder estadístico del 80%, para detectar una reducción del 70% en la colonización con las medidas antisépticas. Un cultivo del líquido de drenaje con un crecimiento bacteriano de 1+ o mayor, fue definido como positivo, sobre la base de la asunción de que el crecimiento sólo en el caldo no sería clínicamente significativo. Se definió el cultivo positivo del tubo de drenaje como un crecimiento de más de 50 CFU, sobre la base de datos previamente publicados, demostrando inflamación en el sitio del catéter en la mayoría de los sujetos con CFU mayor de 50 [15]. Dadas las limitaciones en la selección de esos puntos de corte, los autores examinaron objetivos finales que no dependieran de la elección de puntos de corte para la positividad; la cuantificación ordinal del grado de colonización fue analizada también para los cultivos del líquido y del tubo de drenaje. En las muestras colonizadas por múltiples organismos, el grado más alto de cuantificación, a través de todos los organismos, fue usado para clasificar la muestra para análisis. Las ISQ incluyeron cualquiera de lo siguiente, dentro de los 30 días después de la operación: drenaje purulento, cultivo positivo de material asépticamente recogido de la herida quirúrgica, signos de inflamación con apertura de la incisión y ausencia de cultivo negativo, o diagnóstico de infección por parte del médico (que podía incluir a la celulitis). Los casos de ISQ equívoca fueron revisados en detalle por el equipo de investigación, sin tener conocimiento de la rama de tratamiento asignada y fueron decididos por consenso.

Análisis estadístico

Se realizaron comparaciones de 2 muestras por nivel de paciente, usando las pruebas de t para dos muestras o las pruebas rank sum de Wilcoxon para variables continuas y ordinales y pruebas de probabilidad de 2 para variables nominales. La duración y volumen del drenaje fueron comparados usando modelos lineales de efectos mixtos, para tomar en cuenta a los drenajes múltiples en la paciente. Las tasas de colonización fueron analizadas por nivel de drenaje con modelos lineales mixtos generalizados (regresión logística de intercepción aleatoria), para tomar en cuenta la no independencia de los drenajes múltiples en una misma paciente. Los niveles ordinales de cuantificación de la colonización fueron comparados entre las ramas de tratamiento, usando un enfoque de ecuaciones de estimación generalizada. para adecuar la regresión logística ordinal. También se efectuó un análisis por paciente de la colonización del drenaje, como una comparación de tasas de ISQ, usando las pruebas de 2. Se usó la prueba del signo para proporciones apareadas, para comparar las tasas de positividad entre drenajes de mastectomías y axilares, en pacientes que tenían ambos. Los valores de P < 0,05 fueron considerados estadísticamente significativos. El análisis fue realizado usando el programa SAS (Versión 9.2; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Resultados

Ciento trece pacientes fueron enroladas, siendo 13 de ellas excluidas antes de completarse el estudio, por distintas razones, incluyendo las siguientes: dificultades en retornar para la remoción del drenaje (distancia de viaje/mal clima (6), paciente que había consentido pero que cambió de parecer en el 1º DPO (3), paciente a la que se le prescribió antibióticos entre el momento del consentimiento y la cirugía (2), paciente con reconstrucción inmediata (1) y barrera de lenguaje significativa (1).

Las restantes 100 pacientes con 125 drenajes completaron el estudio. Cuarenta y ocho mujeres (58 drenajes) fueron randomizadas para el grupo de control y 52 mujeres (67 drenajes) para el grupo de antisepsia. Los grupos de control y antisepsia fueron similares con respecto a la edad, IMC, clase de ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists), quimioterapia o radiación previa, tabaquismo, preparación preoperatoria de la piel, tiempo operatorio, día de remoción del drenaje y volumen del drenaje (Tabla 1). La mastectomía total, con o sin biopsia del ganglio linfático centinela, la disección ganglionar axilar y la mastectomía radical modificada, fueron realizadas en 66, 6 y 28 pacientes, respectivamente. La mediana de la duración del uso del drenaje fue de 7 días (rango, 4-19 días), con una mediana del débito de 23 mL (rango, 3-136 mL) en las últimas 24 horas previas a la visita de la 1º semana y una mediana de 19 mL (rango, 3-57 mL) en las 24 horas previas a la remoción del drenaje.

• TABLA 1: Características de la cohorte en estudio (Ver tabla)

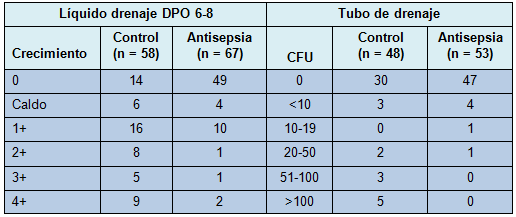

Colonización del líquido de drenaje en la 1º semana

Los cultivos del líquido del bulbo del drenaje a la 1º semana, en el grupo tratado, mostraron significativamente menos crecimiento bacteriano que aquellos del grupo control. En el punto de corte de 1+ ó crecimiento mayor para los cultivos del líquido de drenaje, el 21% (14/67) de los drenajes tratados fueron positivos, comparado con 66% (38/58) de los drenajes de control (P = 0,0001). El análisis realizado sobre una base por paciente mostró un resultado similar, con 13 de 52 (25%) pacientes en la rama de antisepsia experimentando colonización 1+ o mayor en cualquier drenaje, comparado con 31 de 48 (65%) pacientes en la rama de control (P < 0,0001). Para examinar un análisis no dependiente de la elección del punto de corte, el resultado de la cuantificación ordinal fue comparado también entre los 2 grupos (Tabla 2) y demostró nuevamente una fuerte significación estadística (P < 0,0001). En los drenajes removidos después de la visita de la 1º semana, se obtuvo un segundo cultivo al momento de retirarlo. Todos los drenajes positivos (≥ 1+) en la 1° semana, fueron positivos también al momento de la remoción, con al menos 1 organismo en común entre los 2 cultivos, en 11 de 14 (79%),

• TABLA 2: Concentración de la colonización bacteriana para el líquido de drenaje a la 1º semana y para el tubo de drenaje al momento de su remoción, analizada por drenaje.

Colonización del tubo de drenaje

El tubo de drenaje fue cultivado al momento de su remoción en 76 sujetos (96 drenajes; 43 control y 53 antisepsia). Utilizando un valor de corte de 50 CFU, los cultivos del tubo de drenaje fueron positivos en 0% (0/53) de los drenajes tratados, comparado con el 19% (8/43) de los drenajes de control (P = 0,004). En un análisis por paciente, 0 de 40 pacientes en el grupo de antisepsia mostraron una colonización mayor de 50 CFU en cualquier drenaje, comparado con 7 de 36 (19%) pacientes en la rama de control (P = 0,0008). Tratando el grado de colonización como una variable ordinal (ver Tabla 2), se obtuvo también una diferencia estadísticamente significativa entre las ramas de tratamiento (P = 0,04). Los sujetos en el grupo de drenaje con antisepsia tuvieron mucha menos probabilidad de tener altos niveles de colonización bacteriana en el líquido de drenaje y ninguna de ellas tuvo más de 50 CFU en el tubo de drenaje. Entre los drenajes con cultivo del líquido del bulbo positivo (≥ 1+) al momento de la remoción del drenaje, el tubo de drenaje también fue positivo (> 50 CFU) en el 28% de los drenajes de control versus 0% en los drenajes con antisepsia. Contrariamente, entre los 8 drenajes (7 pacientes) con cultivos positivos del tubo (todos en el grupo control), los 8 tuvieron un crecimiento ≥ 1+ en el líquido de drenaje y 7 de 8 tuvieron el mismo organismo en el líquido y en el tubo.

Drenajes múltiples

Veinticinco pacientes (10 control y 15 antisepsia) tuvieron 2 drenajes ipsilaterales. En relación con los cultivos del líquido, los 2 cultivos del líquido del bulbo en la 1º semana fueron concordantes para 20 pares de drenajes (12 negativos, 8 positivos) y discordantes para 5; 4 de los 5 pares de drenajes discordantes fueron positivos (≥ 1+) para el líquido de drenaje de la mastectomía, pero no para el líquido del drenaje axilar. La diferencia en la tasa de positividad no fue significativa (P = 0,38) y la concordancia estadística fue de 0,60. Se observaron resultados similares para los cultivos de los tubos entre los 20 casos con drenaje de la mastectomía y drenaje axilar. Los resultados de los cultivos de los tubos fueron concordantes para 19 pares (18 con ambos cultivos negativos y 1 par con ambos cultivos positivos) y discordante para 1 paciente, que tuvo un drenaje axilar positivo con más de 100 CFU pero con un crecimiento de sólo 20 a 50 CFU en el drenaje de la mastectomía (por debajo de 50 CFU y, por lo tanto, negativo).

Colonización bacteriana y duración del drenaje

En el grupo control, la colonización bacteriana fue un fenómeno tiempo-dependiente y aumentó en frecuencia con la mayor duración de la presencia del drenaje, tanto en el líquido en el bulbo como en el tubo de drenaje. En el grupo con antisepsia, los cultivos positivos del líquido también aumentaron en frecuencia con el tiempo, pero fueron menos frecuentes que los del grupo control en los mismos intervalos de tiempo. Los cultivos de los tubos en el grupo con antisepsia permanecieron negativos en todos los puntos de tiempo.

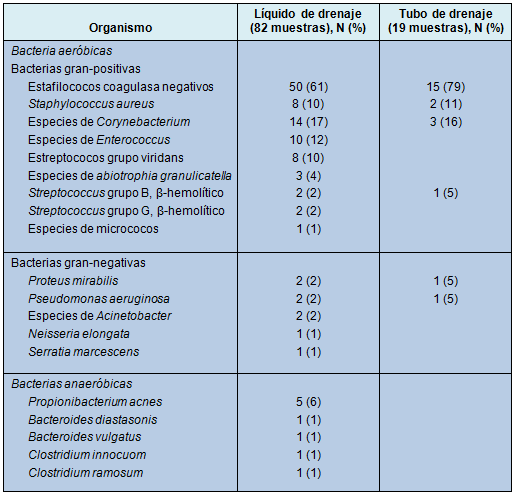

Microbiología

Una amplia variedad de microorganismos fue identificada en el líquido del bulbo, demostrando el 35% de los cultivos organismos múltiples (Tabla 3). Los estafilococos fueron los más comúnmente recuperados (71%), predominantemente los coagulasa negativos con algún Staphylococcus aureus. Los bastones gram-negativos y los anaerobios fueron identificados con menor frecuencia. El tubo de drenaje mostró menor variación en los tipos de microorganismos, siendo las especies de Staphylococcus las más comunes.

• TABLA 3: Prevalencia de aislamientos microbacterianos en los cultivos del líquido de drenaje o de los tubos con colonización

Eritema en el sitio de drenaje y colonización

La extensión del eritema en la piel alrededor del sitio de salida del drenaje como una medición radial, fue significativamente menor entre los sujetos en el grupo de antisepsia que en el grupo control (media 1,1 mm vs 2,6 mm; P = 0,001) en la 1º semana. Aunque los drenajes con cultivos de los tubos positivos (> 50 CFU) tuvieron, en promedio, un mayor eritema en el sitio del drenaje (media 4,4 mm vs 1,1 mm; P = 0,86), así como los pacientes con ISQ (media 3,0 mm vs 2,1 mm; P = 0,41), ninguna de esas comparaciones alcanzó significación estadística.

Infecciones del sitio quirúrgico

La ISQ fue diagnosticada en 6 pacientes: 5 en el grupo control y 1 en el grupo de antisepsia. De las 5 pacientes con ISQ en el grupo control, 2 tuvieron abscesos que requirieron incisión y drenaje y una tercera demostró celulitis con cultivo positivo. Las restantes 2 pacientes con ISQ tuvieron casos de celulitis sin cultivos, pero al momento del tratamiento fueron consideradas por un médico, ciego en relación con el estudio, como presentando infección, siendo tratadas con antibióticos y mejorando con la antibioticoterapia, por lo que en la revisión final fueron consideradas como ISQ.

Hubo 1 sólo caso de ISQ en el grupo con antisepsia del drenaje, que presentó síntomas en el 31º DPO. La paciente había comenzado con quimioterapia en el 21° DPO y presentó fiebre de origen desconocido el 31º DPO, con desarrollo de signos localizados de infección axilar en la siguiente semana, que llevaron a la incisión y drenaje de un absceso axilar. Dado que los síntomas de la paciente comenzaron justo después del marco de 30 días, estandarizado en la definición de los Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, es discutible si esa ISQ debería o no ser incluida, pero los autores la incluyeron para una evaluación conservadora de las diferencias entre los grupos de control y de antisepsia. Por lo tanto, con 5 ISQ entre 48 mujeres en el grupo de control y 1 ISQ entre 52 sujetos en el grupo de antisepsia, la diferencia en la tasa de ISQ entre los 2 grupos (10,4% vs 1,9%) no fue estadísticamente significativa, pero mostró una fuerte tendencia (P = 0,06). Si ese caso de ISQ en el grupo de antisepsia es excluido por su ocurrencia después de los 30 días, entonces la tasa de ISQ en el grupo control (10,4%) es significativamente más alta que en el grupo de antisepsia (0%), P = 0,01.

Correlación de la ISQ y el grado de colonización del drenaje

Aunque el análisis estuvo limitado por el número pequeño de ISQ, la tendencia fue que la ISQ ocurrió más frecuentemente entre los sujetos con colonización bacteriana más grande, tanto en el líquido del drenaje como en el tubo de drenaje, comparado con aquellos con menor colonización o sin colonización bacteriana. Entre las pacientes con severo crecimiento bacteriano (4+) en el líquido del drenaje, de cualquiera de los drenajes, en la 1º semana, la tasa de ISQ fue de 2 sobre 9 (22%), comparado con la de los crecimientos menos severos o sin crecimiento (4/91 = 4%; P = 0,08). Similarmente, la tasa de ISQ fue de 2 sobre 7 (29%) para las pacientes con crecimiento en el tubo mayor de 50 CFU en cualquiera de los drenajes, comparada con 3 de 69 (4%) pacientes con CFU menor o sin crecimiento bacteriano (P = 0,05).

Toxicidad de la intervención y acatamiento

No hubo reacciones alérgicas al disco de clorhexidina. El acatamiento o cumplimiento con las intervenciones antisépticas fue excelente, basado en los reportes de los sujetos; en la visita a la 1º semana de seguimiento y más allá, no hubo sujetos que reportaran ninguna falla en el cumplimiento con las intervenciones. Dos pacientes se sintieron inseguras sobre su habilidad para realizar el cambio del disco y ambas retornaron a la Clínica para ser asistidas por el coordinador del estudio en el primero de los cambios: una de ellas realizó los cambios independientemente después de ello y la otra eligió retornar para la asistencia del coordinador en los restantes cambios.

Discusión

En este estudio, los autores demostraron que las medidas locales de antisepsia reducen significativamente la colonización bacteriana de los drenajes quirúrgicos después de la cirugía mamaria y axilar, tanto en el líquido del bulbo del drenaje como en la porción subcutánea del tubo de drenaje. Este trabajo brinda un principio de prueba de que las medidas simples y económicas de cuidado local merecen un estudio adicional en ensayos clínicos como una medida para reducir la ISQ. La ISQ resulta en un aumento de los costos y de la morbilidad y, por lo tanto, ha ganado atención nacional, con programas establecidos para minimizar esos eventos [16,17].

La frecuencia de la ISQ después de la cirugía mamaria y axilar en muchos estudios es más alta de lo que podría esperarse para casos “limpios” [1-6]. En 2 estudios prospectivos multicéntricos recientes, las tasas de ISQ después de la disección axilar (incluyendo casos de celulitis) fueron del 8% y 14% [18,19]. Las razones para esas tasas más altas de lo esperado permanecen indefinidas, pero probablemente son multifactoriales. Además de las diferencias verdaderas en la tasa de ISQ, pueden existir también diferencias aparentes a causa de la definición de ISQ (por ej., si los casos de celulitis deben ser incluidos o excluidos) [20] y de los diferentes métodos de vigilancia para verificar los casos de ISQ [9,21].

La existencia de un drenaje quirúrgico y su presencia prolongada han sido asociadas con un riesgo aumentado de infección [5,9,10], lo que es lógico porque los drenajes quirúrgicos brindan un conducto para la entrada bacteriana dentro del entorno de la herida quirúrgica. Un estudio reciente investigó las tasas de colonización bacteriana en los drenajes quirúrgicos después de una mastectomía y halló que el líquido de drenaje está colonizado por bacterias en el 33% de los drenajes 1 semana después de la mastectomía y en el 81% a las 2 semanas [22]. Asimismo, entre los pacientes que desarrollaron una ISQ, el microorganismo identificado fue el mismo que el previamente identificado en los cultivos del líquido de drenaje, en el 85% de los casos. Esos hallazgos implican con fuerza que el drenaje quirúrgico es una fuente de bacterias que contribuye a la ISQ.

Muchos factores de riesgo asociados con la ISQ, después de procedimiento quirúrgicos en la mama y en la axila, están relacionados con el huésped (IMC, diabetes, tabaquismo, etc.) [6-9], pero pocos de ellos pueden ser modificados dentro del marco de tiempo preoperatorio de unas pocas semanas, que es común después del diagnóstico de un cáncer de mama en estadio temprano. No obstante, la presencia y duración de un drenaje quirúrgico son factores clínicos que pueden ser modificados para reducir el riesgo de infección. Los drenajes quirúrgicos pueden ser removidos más tempranamente en el curso postoperatorio u omitidos por completo, pero el beneficio teórico de riesgo reducido de infección sin drenajes podría resultar en un aumento en la frecuencia de formación de seromas [23-25], lo que – a su vez – ha sido asociado también con un riesgo aumentado de ISQ [26]. Por lo tanto, trabajando con la presunción de que los drenajes después de la mastectomía y de la disección axilar son necesarios y brindan una fuente de ingreso bacteriano, relacionado causalmente con la ISQ [22], los autores del presente trabajo hipotetizaron que, mitigando la colonización bacteriana de los drenajes, se podría ayudar a reducir la ISQ.

Aunque algunos cirujanos prescriben antibióticos sistémicos en el período postoperatorio después de la mastectomía, con la intención de reducir el riesgo de infección asociado con los drenajes implantados [27,28], la eficacia de esa estrategia no está probada y acarrea otros riesgos [29,30]. En consecuencia, los autores de este trabajo seleccionaron un abordaje con medidas antisépticas locales, para minimizar la carga bacteriana del drenaje y de la herida subcutánea.

La antisepsia local para los drenajes implantados es lógica y se extrapola sobre la base de una extensa experiencia con su uso para prevenir las infecciones relacionadas con los catéteres intravasculares (IRC). La investigación sobre las IRC demuestra que la mayoría de las infecciones con dispositivos intravasculares de corta duración, está relacionada con la migración extraluminal de bacterias a lo largo del catéter, mientras que la contaminación intraluminal es responsable por las infecciones en dispositivos intravasculares más permanentes [31]. La reducción de las IRC es abordada exitosamente con un enfoque de intervenciones que apuntan a ambas rutas de acceso bacteriano [32]. En el caso de los drenajes quirúrgicos, la bacteria puede acceder también al entorno de la herida quirúrgica, tanto por vía extraluminal como intraluminal; las contribuciones relativas de esas rutas al riesgo de la ISQ es desconocida. Por esa razón, se usó en este ensayo el principio de prueba del abordaje antiséptico apuntando tanto a la colonización extraluminal como a la intraluminal. La curación con disco de clorhexidina fue incluida sobre la base de la evidencia existente sobre su eficacia en reducir las IRC [33,34]. Además del disco de clorhexidina, se añadieron los lavados con hipoclorito del bulbo del drenaje, un reservorio que es abierto intermitentemente hacia el medio ambiente externo, para su vaciamiento. Esa intervención fue incluida sobre la base de evidencia de la reducción de la bacteriuria después de la irrigación con ácido acético de los reservorios de drenaje urinario, en los pacientes con catéteres uretrales implantados por largo tiempo [35]. La solución de Dakin diluida, para la irrigación del bulbo del drenaje, fue seleccionada para su uso a causa de su amplio espectro antimicrobiano, su empleo tradicional en la práctica clínica para las heridas infectadas y su bajo perfil de toxicidad [36-38].

Los datos de este trabajo demuestran que la colonización bacteriana del bulbo del drenaje y de la parte subcutánea del tubo de drenaje puede ser reducida con medidas antisépticas locales no tóxicas. Los hallazgos también sugieren que eso puede trasladarse a una reducción de las tasas de ISQ. Sin embargo, los hallazgos deben ser interpretados con la adecuada precaución, porque este estudio no fue potenciado para un objetivo final primario de ISQ y los hallazgos sobre ISQ no alcanzaron significación estadística. Por lo tanto, aunque los hallazgos son alentadores, los autores no pueden asumir que esas intervenciones reducirán la ISQ. Asimismo, aunque las intervenciones antisépticas redujeron dramáticamente la colonización bacteriana de los drenajes quirúrgicos, los resultados de los cultivos variaron en el pequeño número de ISQ que ocurrieron, con algunos individuos desarrollando infección en presencia de líquido de drenaje negativo y tubos de drenaje en situación inversa; un pequeño número de individuos con “severo” crecimiento bacteriano que no desarrolló infección. Es tentador especular que esos hallazgos sugieren factores del huésped y que probablemente juegan un rol importante en el desarrollo de la ISQ. Los individuos con factores que confieren un riesgo aumentado (IMC incrementado, tabaquismo, inmunosupresión) pudieron tener umbrales más bajos para la carga de bacterias que puede ser tolerada antes de manifestarse como una infección clínica. Este estudio no estuvo potenciado para analizar separadamente esos subconjuntos. Otra limitación de este estudio es la combinación de 2 intervenciones para manejar el posible ingreso bacteriano, en el entorno de la mastectomía/disección axilar, por lo que los autores no pudieron determinar la contribución relativa de cara ruta de contaminación para la ISQ y no pudieron evaluar los efectos independientes de cada intervención.

Esas intervenciones son simples de realizar, fáciles de aprender, tienen baja toxicidad y son relativamente baratas. Esos métodos podrían aplicarse también a otros procedimientos quirúrgicos en los que los drenajes son requeridos y en los que las consecuencias de la infección son altas, por ejemplo, disección inguinal, reparación de eventración con malla y reconstrucción mamaria con implantes. Con el principio de prueba de que la antisepsia de los drenajes puede reducir la ISQ mediante la reducción de la colonización bacteriana de los drenajes, los autores tiene la intención de realizar un ensayo randomizado más grande, potenciado para el objetivo final de la ISQ.

♦ Comentario y resumen objetivo: Dr. Rodolfo D. Altrudi